Scandal in Hyderabad! India in Translation. Reading Through Each of India’s 28 States - Telangana - SIN

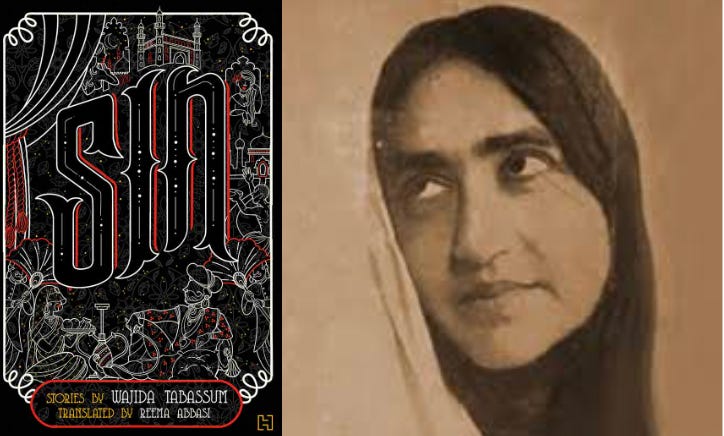

The fifth in my series — SIN by Wajida Tabassum

SIN by Wajida Tabassum

STATE: Telangana

Original Language: Urdu

First published in a number of different Indian literary journals in the 70s in Urdu

Publisher in English — Hachette India (2022) - Link

Translated by Reema Abbassi, a Pakistani journalist.

—-

The mansion was brimming with flurried activity and a babble of happy voices. Maids with silver and crystal trays charged through the labyrinth of hallways.

Sounds good, right? Trust me. Something awful is about to happen.

When I set out on this journey, I said ‘novels’ but it was worth breaking the rules for this short story collection written originally in Urdu filled with the erotic scandal of aristocratic old Hyderabad. It’s Hyderabad in the 1950s but except for some references to ‘cars’ and ‘office’, you could easily see yourself behind the purdah in the Nawab’s palace in 1700 because that’s where the women of Tabassum’s fiction are perpetually imprisoned.

There’s over 20 stories in the collection and the world Tabassum creates has certain non-negotiable features:

— Unrelenting Gender Norms

— Brick & Mortar Feudalism

—- Out-of-control Lust

A typical Tabassum story may run this way.

A young girl from a pious but not wealthy family is spotted by a rich chote nawab, some aristocratic princeling. He either marries her and is then serially unfaithful to her. Or, he seduces her and then refuses to marry her. Or, worst of all, he marries her but turns out to have no interest in consummating. Now, if this makes it sound formulaic, I apologize. With the obvious control of a great storyteller, Tabassum contorts and folds these tropes onto themselves like a master tailor and, usually, among the layers, there’s a hidden needle.

Tabassum generated a lot of controversy in her own lifetime and her extended family tried to silence her; the obvious reason was the erotic nature of these stories. I suspect there was an even greater fear of her because of a shimmering power beneath the surface that would have made her dangerous in her own time —- rage.

Her writing pulses with hostility and deep feeling; you feel the absolute rage of her female characters; they are smoldering, in all understandings of the world, and in their rage, they’re capable of practically anything, certainly a host of anythings that their husbands would think beyond their capacity, such as cheating on them with servants.

It’s very gratifying to see Tabassum write directly into the inherent issues in servant-master-mistress dynamics.

All you have to do is look at the Aarushi Talwar - Hemraj Banjada double murder in 2008 and you will see that right beneath the surface — similarly to the way it was in the Antebellum South — Indians (and perhaps this extends to other South Asians, too, but I can’t say for sure) — have dual fantasy/horror with their domestic staff — there’s fear of sexual assault and of murder/robbery — but in Tabassum’s work, there is the other fear —- in the old Hyderabad at least, these aristocratic old money Muslim families have many, many servants and they are treated as possessions and the men of the house frequently ‘possess’ the younger female staff, much to the fury of their wives.

It’s this dynamic that Tabassum frequently explores and you can see why she caused so much consternation at the time. These are big taboos to even mention and she wrote fearlessly into them, exposing them, normalizing them, and in that normalizing, provoking even more shock.

In terms of literary value, there’s so much to learn from Tabassum:

She wastes no time. She moves time aggressively, jumping the narrative from scene to key scene. Often, those key scenes have a cinematic quality. The male lead says something and she gives us one telling physical detail. The female lead has a devastating response and some scent lingers in the room and the scene is over.

Managing the tightrope walk of ‘over-writing’ — across 22 stories, there are so many heart-wrenching scenes of high drama, scenes of betrayal and confrontation — and while they may blend a bit in terms of context and characters, the pain of each wound feels fresh, each time a different knife plunges into the same wound. How does she do it? I think the answer here is beyond the technical. Among the 22 stories, there is a single autobiographical one. It’s evident that she lived feelingly; there was no numbness in her. And, though I’m hesitant to use a retrospective lens on her, so many of these stories feel like varied explorations of some single endured trauma. Her acute sensitivity and the fact that emotions never seem to dull for her pack each of her stories with explosive charge.

But now, for Hindi and Urdu speakers, I have a lovely treat. God bless Youtube. Here, from 1991, is the wonderful Wajida herself delivering her shayari, Urdu poetry. It’s a video to be relished and it also opened a window for me into a culture I didn’t know existed. The next time I go home to India, I hope to go to one such mashaira event. It looks incredible.

Here’s the video — LINK

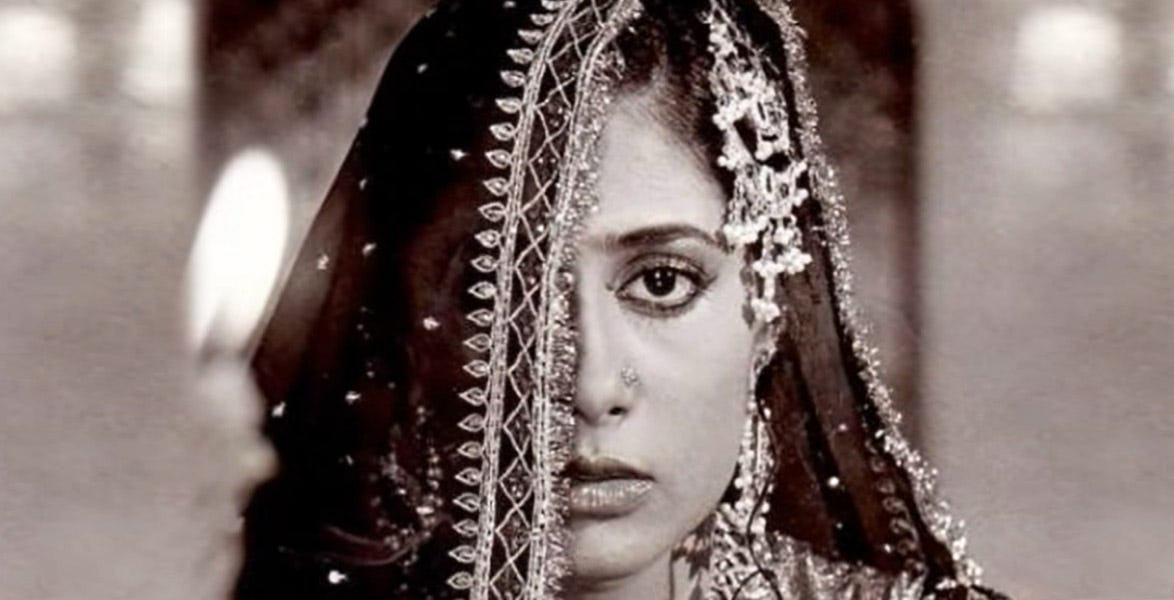

I also want to acknowledge the excellent review of ‘Sin’ by Paramita Ghosh that I enjoyed reading. For her banner picture, she chose this image of Smita Patil from a movie called 'Bazaar' (1982), a film set in Hyderabad, that apparently highlighted the issue of bride-buying. This still captures the terror, anticipation, resignation, and inner resolve of the female characters of Tabassum’s world.

It’s also appropriate that she chose Smita Patil, a cult icon who died in a plane crash and who, during her lifetime, was seen as a home-wrecker for having a very public affair with Raj Babbar whose wife Nadira chose to stay with him through it all. It was an ugly situation all around and you sense that it was caused by man who wanted it both ways and ended up hurting everyone.

Wajida Tabassum’s characters lived the ‘operatic’ qualities of the domestic soap opera but there’s no regurgitated plotlines here, only fresh tragedies. And though these stories are fifty years old, their freshness lingers like jasmine oil in the hair of a bride waiting in the chamber for her disappointing husband to make an unwelcome entrance.

Stars: 5/5.

Read the other posts in this series.

Tamil Nadu - Pyre - LINK

Karnataka - Samskara: Rites for a Dead Man - LINK

Andhra Pradesh - Yashodhara - LINK

Kerala - The Legends of Khasak - LINK