Johan Cryuff

What to do with nuestros momentos dados

I was thinking about Johan Cryuff today and that’s not unusual. I think about him most days. Of course, I never saw him play but I’ve always liked the idea of Johan Cryuff. I think it’s because deep down I don’t care about winning; I think winning is less romantic than losing beautifully and Cryuff epitomizes this but also I love words and Cryuff had a remarkable facility with words. Here’s how wikipedia explains how Cryuff-isms are perceived in Dutch -- semantically, Cruijffiaans contains many tautologies and paradoxes that, while appearing mundane or self-evident, suggest a deeper level of meaning

“Before I make a mistake, I don’t make that mistake.”

“If I wanted you to understand it, I would have explained it better.

And the brilliant quote that appears to be about football but is about so, so much more:

When you play a match, it is statistically proven that players actually have the ball 3 minutes on average … So, the most important thing is: what do you do during those 87 minutes when you do not have the ball. That is what determines whether you’re a good player or not.

This applies so well to writers; we can’t be writing every moment of the day and yet, as we go about our days, it’s what we do, the quality of our observation, what we notice and preserve for when we return to the desk, that is of vital importance. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if that 87:3 ratio was more or less accurate to writers, too!

Anyway, forget writing. Back to Cryuff. I’ve always admired his bearing and his posture and his classic Dutch matter-of-factness that can appear as arrogance and yet he managed to be charming in a way that is quite unDutch, too.

When T and I went to Amsterdam many years ago, it was soon after he had died. He died at only 68 of lung cancer; he smoked for much of his life. T and I were staying in a houseboat far from everything and the one thing I wanted to do was visit the Cryuff statue and lay my handwritten tribute among the flowers and other tributes. She humored me, as she often does; I try not to give into excessive sentimentality but I did then.

Across the world, countries are re-litigating multiculturalism and assimilation and it’s worth remembering two of the ways a Dutchman became beloved in Barcelona, in Catalunya, his adopted home.

Famously, he named his son Jordi at a time when that name, the name of Catalunya’s patron saint, was prohibited by Franco’s government; naturally, he, a foreigner, gave such a name to his son and endeared him immensely to the Catalans.

But also, in press conferences, he spoke Spanish in his own distinctive way, replete with his own Cruijffiaans (Dutch for Cryuff-isms. He intentionally didn’t speak Catalan in interviews, saying he wanted the interviewers to struggle to understand him and not the other way around. Once in a press conference, while struggling to find his words, he coined a memorable phrase:

“En un momento dado....”

In a given moment.

He may have been trying to say a precise moment but this odd formulation, a given moment, as if someone has made a present of a moment, endeared him to the people of his adopted home and became a quotable line.

I don’t fully know where I am going with this but I have talked elsewhere about ceterapatriotism, love of a country that is not our own. I think a couple of foolproof ways to show ceterapatriotism is a) respect local objects of reverence and b) make an honest effort to engage with the language because words are always objects of intimate regard.

Of course, in Cryuff’s case, it also helped that he was an international superstar, looked like a Beatle, and was really really good at football. Still, it’s quite amazing that he fell in love with a city and a people and they loved him back!

Thank You

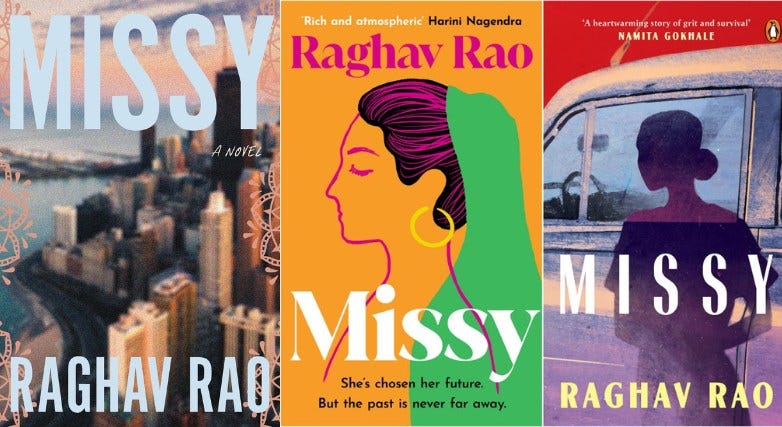

If you have read MISSY and enjoyed it, then please leave a review and rating on Goodreads and Amazon. You may think it inconsequential; but it helps.

To buy Missy, here are the relevant links. North America. UK. India.

Cruyff was special in that like Zidane and Messi, he was not only magic on the pitch, but he also won often enough that his magic is endowed with momentary and spectacular brilliance in memory. This can also be said of outrageously gifted players like Dennis Bergkamp, Neymar, Michael Laudrup, Andres Iniesta; those cast as misunderstood geniuses like Dimitar Berbatov, Eric Cantona; and even current maestros like Pedri and Phil Foden. All magic, and all winners.

But then there is the player who we all knew had the undeniable spark, capable of drawing a collective gasp from all watching at any moment during a game, but whom we remember best with their hands on their hips after a match, eyes big and empty, mouth drawn tight or open in shock. Just a few players I've seen who lost beautifully.

Denilson

Francesco Totti

Juan Roman Riquelme

Santi Cazorla

Rui Costa

Roberto Baggio

Juan Carlos Valeron

Hidetoshi Nakata